Established in the late 18th century by Eli Whitney, and revered by most as an impactful mechanism that spurred the American economy to life, The Cotton Gin, had exponentially decreased the time it took to produce seedless cotton fibers, allowing the market of cotton-produced textiles to become all the more in demand, and ultimately expanded the commerce of cotton and cotton dependent goods nationally, and internationally.

But what was the moral cost of such a highly valued instrument, and how does this reflect our overarching need for material goods?

In this sense, the Cotton Gin isn’t so different from modern technology or even the social media apps we use today.

Consumerism, naturally, has kept itself up to date with the current demands and interests of the public, much like social media platforms, but the moral high ground of the concept has historically been a largely vague topic of debate, the cotton gin being just one example of the heinous cost of morality that consumerism has plagued upon us.

Consumerism has blurred the lines between what’s right or wrong within Western culture, therefore impacting how we view material goods, and the services that produce them.

For example, the second industrial revolution not only heavily impacted the economy but also shaped how ethics are sacrificed for material goods.

The beginning of the second industrial revolution in the U.S., 1870-1914, sparked a debate centered around ethics in the workplace. Oftentimes, children were working in harsh conditions, working anywhere from twelve to fourteen hours a day, and the 1900 US census counted two million children working factories, mills, mines, cotton fields, and on the streets.

Many of the people within these workplaces suffered life threatening injuries or even death, with the 1913 Bureau of Labor Statistics recording around 23,000 industrial deaths, equivalent to 61 deaths per 100,000 employees.

The variety of enterprises afforded to the urban, industrialized cities in America at the time heavily impacted the economy and sacrificed the duality between morality and good ethics for material goods. This shift highlighted the difference between a more agrarian lifestyle to one of work for wages.

Following this current, the second industrial revolution offered more opportunities for minority groups, especially for African Americans originated in the South.

The first phase of The Great Migration, from 1910-1940, gave African Americans the chance to escape racial violence and pursue economic and educational opportunities. This phase relocated African American Southerners to heavily industrialized cities like New York, Chicago, Detroit, and Pittsburgh, and when the WWI effort increased, this allowed African Americans the opportunities to supply labor in non-agricultural areas.

However, this phase of The Great Migration also increased tensions surrounding prejudice in the North and South which resulted in mass forms of violence against African Americans like The Red Summer of 1919.

Much like how Social media has expanded our knowledge surrounding modern technology, and afforded younger generations with more extensive work opportunities, WWII also expanded labor and work opportunities for African Americans.

However, they were still widely limited and secluded to service and labor work like cooks, road builders, and supply unloaders, while still battling racism and discrimination within the country due to existing black codes, which later developed into Jim Crow laws. Although new opportunities to experience work can be seen as a good thing, it can also allow the spread of discriminatory exploitation, further influencing social standings we see today.

It seems as though the exploitation of minority groups, whether racially or sexually, by companies and overall industries that capitalize from things like beauty, music, or retail sales is acceptable as long as you get your Stanley cups and overpriced sneakers.

Now, it’s no secret that consumerism has been at the forefront of America’s origin. In fact, settlers of Jamestown sought after profit so much that it kickstarted the movement of slave labor in Northern America.

In 1610, John Rolfe, an English explorer, brought tobacco seeds to the English colony of Virginia, which ultimately became the first crop of the English Atlantic trade.

Just nine years later, in 1619, the first enslaved Africans stepped foot on the shores of Fort Monroe in Hampton, Virginia.

This sparked the presence, necessity of consumerism, and privilege of material goods that built every aspect of the social biases that we see today.

This also impacts the question of morality vs. consumerism in terms of the causation of the domestic slave trade within the U.S.

Following the invention and patenting of the Cotton Gin, to meet the demand of cash crops (like sugarcane, rice, and tobacco) planters turned to traders who imported enslaved individuals to the colonies. As the number of enslaved African Americans in the U.S. grew, so did the concept of The Slave-Auction, or open markets that inspected humans like animals and sold them to the highest bidder.

As agricultural demand increased it allowed for enslaved labor to become entrenched in the Southern states. So much so, that the reliance of human bondage had trumped the ethics surrounding labor as a whole, and even The Declaration of Independence itself.

The claim of “All men are created equal…” proved to be a form of selective enforcement by the government; equality only applies to those who aren’t forced to work for it.

“Slave trading was a “game.” The men, Isaac Franklin and John Armfield, were daring “pirates” or “one-eyed men,” a euphemism for their penises. The women they bought and sold were “fancy maids,” a term signifying youth, beauty and potential for sexual exploitation — by buyers or the traders themselves. Rapes happened often,” confirms the Washington Post.

This also commonly impacted narratives surrounding race, and African Americans, in the western world as a whole.

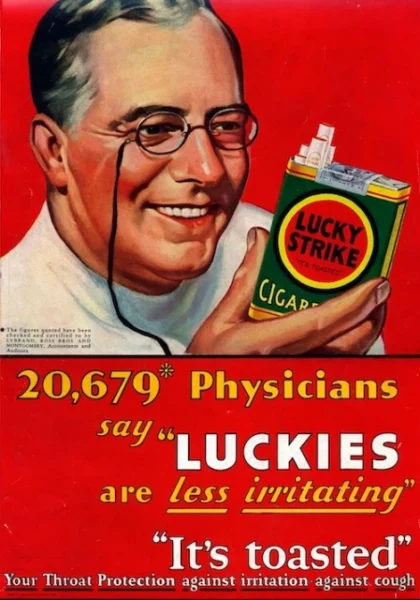

Carried on the back of racial inequality and inequity, consumerism and moral ambiguity reached new heights during the 1920s with every new product that hit the markets.

Daily work seemed to transform itself with new technological and scientific advances like penicillin, the television, radio, traffic lights, polygraphs, etc.

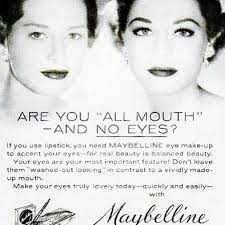

However, the real issues lie in the marketing and promotion of many products within each industry.

The boost in economic growth, especially in the North due to The Great Migration, allowed more industries to profit off of mass production. More specifically, technological advances allowed for industries to reach audiences all across the nation, through the increase in ad presence and promotion.

In fact, with more people investing in the stock market, buying material goods on credit, enabled the dependence and attachment to money that shaped many social and political narratives during the time, one of the most prevalent being the beauty industry’s impact on beauty standards that we still see today.

With beauty markets in the U.S. increasing from 560 in 1950 to 5,670 in just 16 years, consumerism has proven to shape narratives surrounding how people view themselves in order to make a profit.

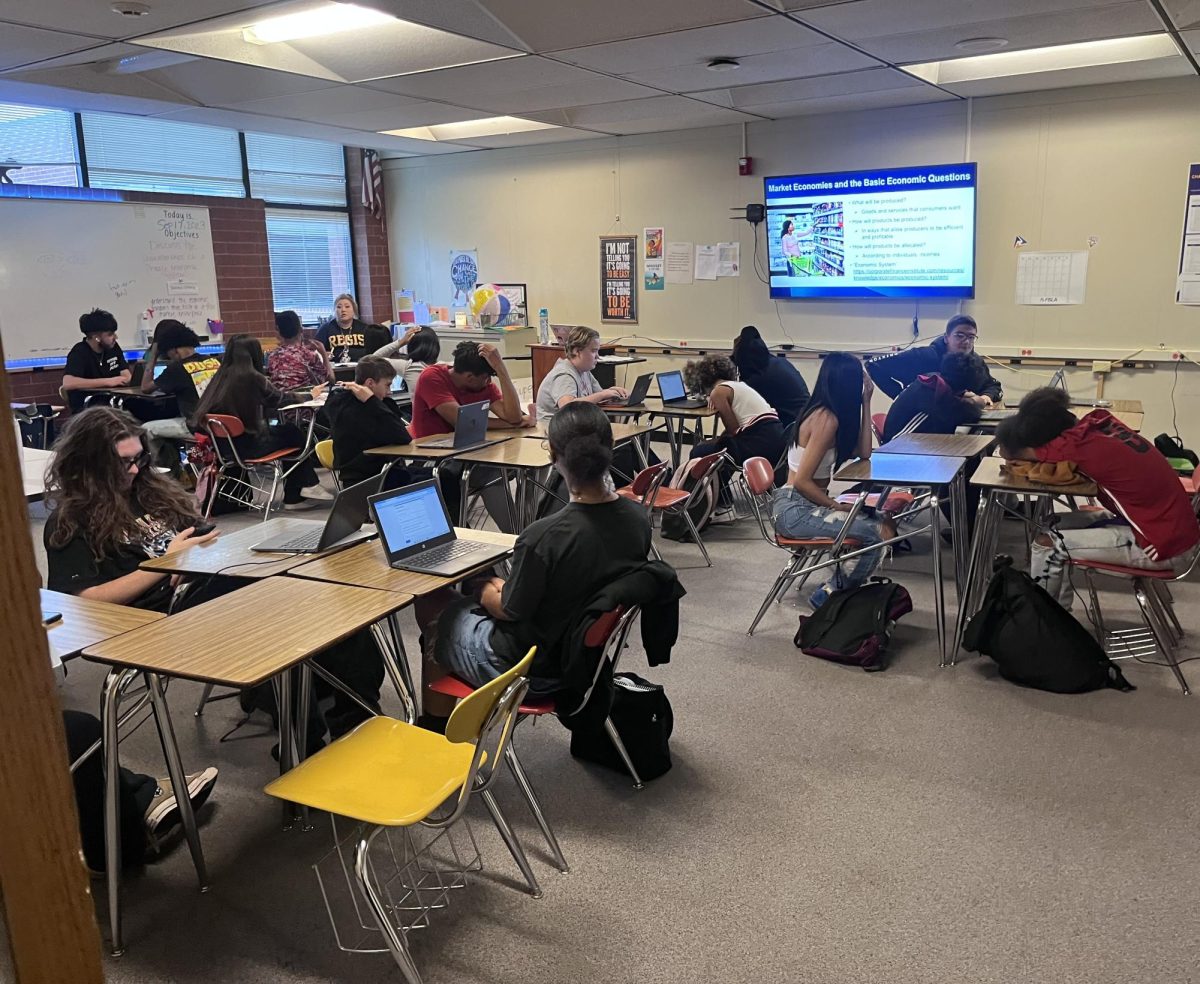

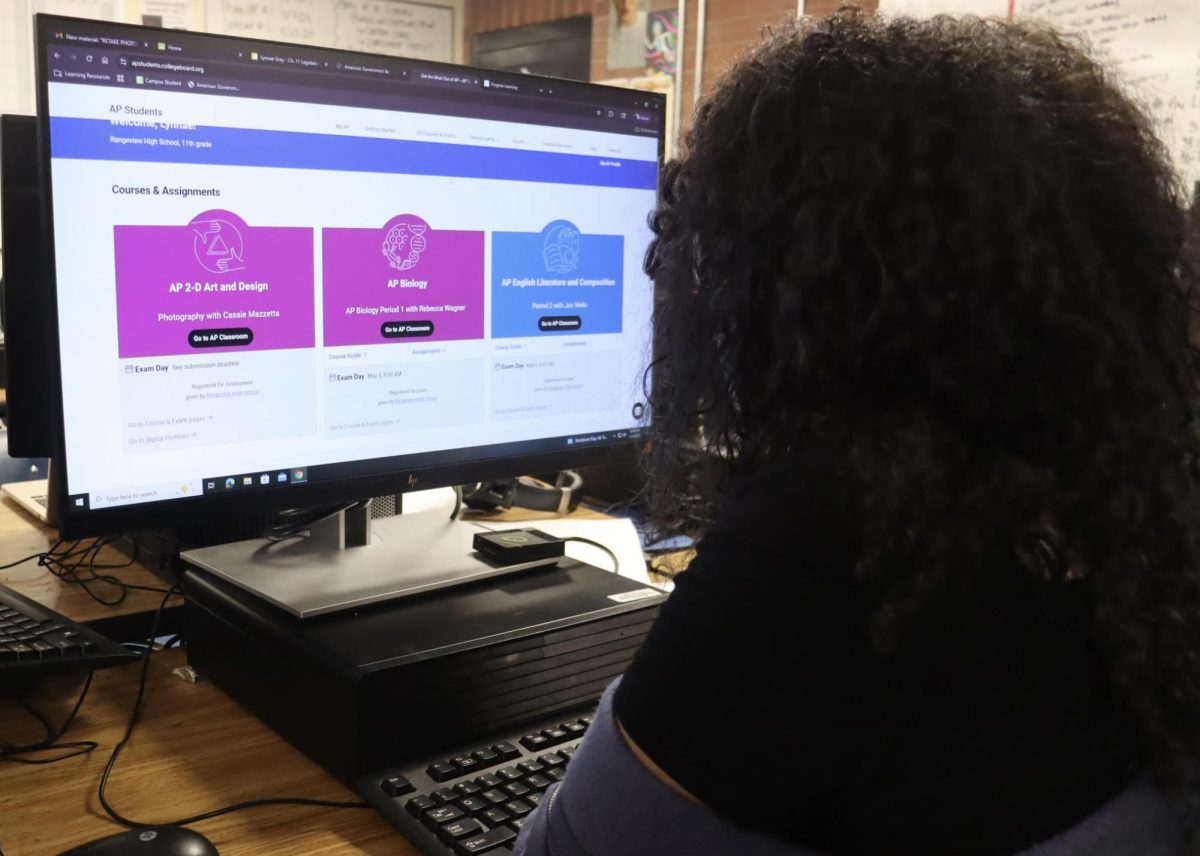

The spread of consumerism in the U.S. was especially present in the early 2000s, and heavily impacted the social climates across many cities and states around the country, influencing how people view not only beauty standards but how they glamorize companies, corporations, and industries as a whole.

With new and more fashionable public figures, like Paris Hilton, Kim Kardashian, and Nicki Minaj surfacing during the time, the narratives surrounding women’s beauty standards were also rapidly changing.

As per usual, many women wanted to be seen as desirable, beautiful, and with an average growth rate of 3.86% each year since 2000, the beauty industry has been capitalizing on these traits for decades.

Even today plastic surgery and cosmetic reconstructive surgeries are on the rise. Liposuction patients aged 19 and below reached a high of 3,080 last year, and Neuromodulator injection, like botox, surgeries reached a whopping 25,308, with a 75% increase from 2019.

“I had a bump on the bridge of my nose and yearned for a tiny, smooth, upturned ‘pixie’ nose,” …“I regret having it done. I was too young to make that decision. My brain and worldview were not developed.”- huff post.

Beauty standards aren’t the only thing heavily impacted by consumerism. In fact, the clothing industry has since become subject to ever changing technologies and trends.

With platforms like Instagram and YouTube reaching height popularity in the late 2000s and early 2010s, fashion trends would forever be influenced by the public eye.

In recent years, TikTok has become a main source for the production and marketing of what many news organizations call Fast Fashion.

Many companies like Shein, Fashion Nova, Cider, Forever 21, ASOS, PrettyLittleThing, etc, have capitalized on these quickly progressing trends, often at the expense of ethics.

Often workers in these textile factories are underpaid and overworked, “The fast fashion industry employs approximately 75 million factory workers worldwide. Of those workers it is estimated that less than 2% of them make a living wage…Many garment workers are working up to 16 hours a day, 7 days a week. The textile industry also uses child labor particularly because it is often low skilled, so children can be exploited at a younger age.” Writes Emma Ross for George Washington University.

Now personally, that sounds pretty similar to the working conditions we know existed at the beginning of the 20th century in the U.S.

The Western world and overall culture has sullied itself by its dependency for material goods all in the name of a hierarchical class system.

With companies and industries capitalizing off of the sociocultural narratives that shape our perceptions surrounding ideal imagery, consumerism in American society is being fed by the cargo ship. Naturally, something that has had such an integral part to play in the formation of the American economy —Jamestown and tobacco, the South and cotton, the North and industrialization, you name it— it’s hard to stray from all the ad presence, societal beauty standards, or even the lack of morality that surrounds consumerism.

These concepts also leave little room to hope for the revival of morality behind the marketing world, “An ethical advertisement is honest, accurate, and strives for human dignity.” defines Microsoft on the topic of ethical marketing.

But have we actually achieved this sense of righteous advertising in our everyday production? What are we actually doing to prove to each other that material goods don’t have to come at such a dire, desolative cost? If we have to even ask ourselves this, is that overpriced, outsourced pair of jeans even worth it? Is that twenty pack of makeup brushes you saw on TikTok Shop worth the dignity and toil of the person who made them worth it if you know you only need four of them?

The clutch that consumerism has had on the Western world has become a vice, gripping onto the throat of our influence and squeezing out the life of our personal values.

Brands that are suspected to illegally source products as a result of forced labor.