Feature Photo By: Dominique Harlan – Senior Ethan Fray sits in the commons while discussing the use of the word nigga at Rangeview. “I say it because it’s like slang to me, [black people have] changed the meaning of the word. But honestly, I feel like no race should say it,” said Fray.

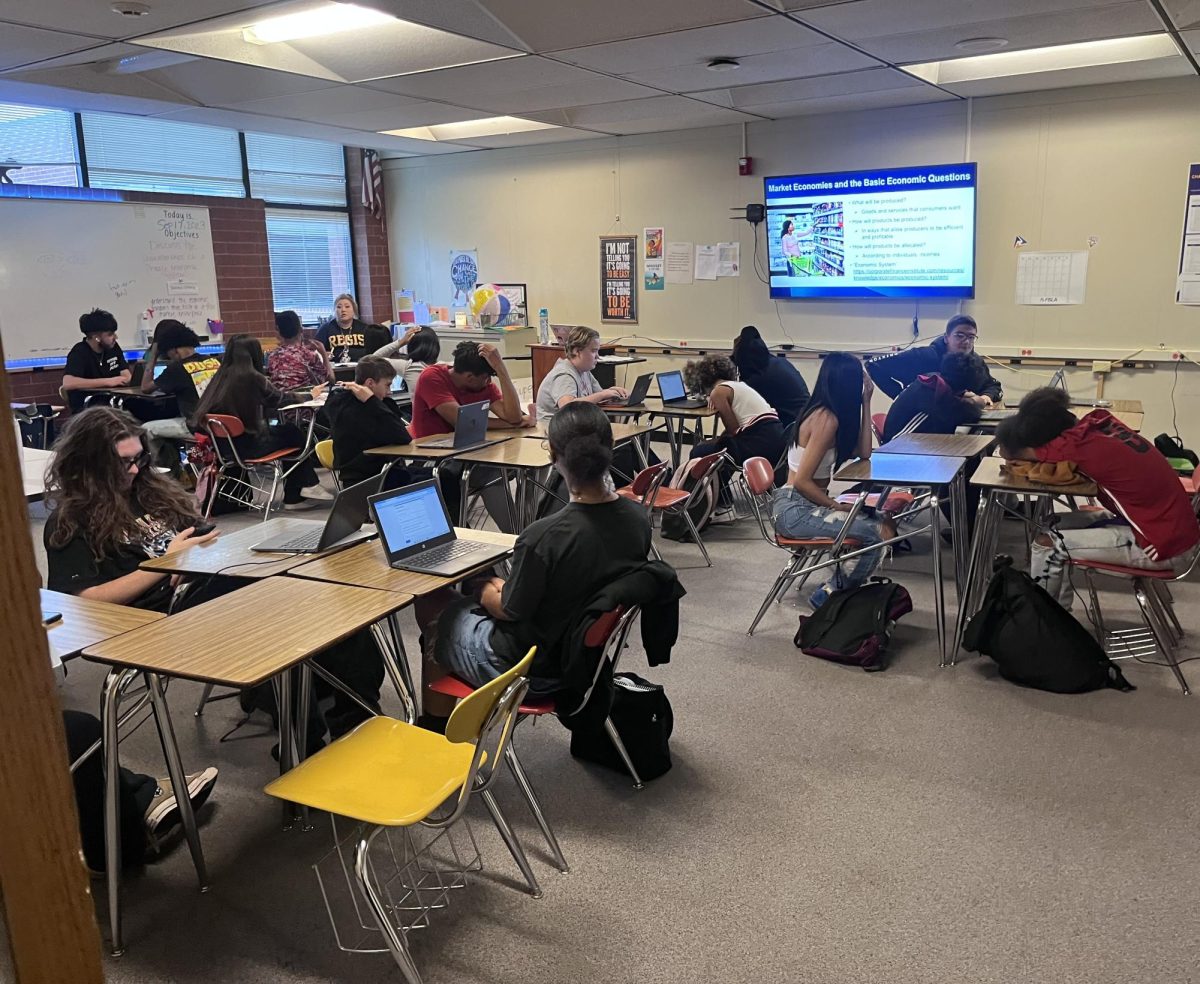

Editor’s note: Throughout this opinion piece are pictures of students and Rangeview staff with their own opinions on the use of the word “nigga.”

If you are not black, do not say nigga.

The black friend you have that lets you say it is not an excuse. The fact that you feel like it is just a word is not an excuse. The fact that you grew up in an area where people say/said it all the time around you is not an excuse.

The truth is that there are no excuses, there are no exceptions and the word is not conditional — if you are not black, (white, Asian, Latinx, Arab, or any other race that identifies as not black) it is not yours to use.

Yes, that still means you, even if your skin is brown.

Several points have to be made in this article in order to understand how words evolve, the history of the term itself, why a race can reclaim a word and why it is not just a word.

Do not read this in an attempt to not understand, respond with fits of anger and/or ignorance. If by the end of this you did not at least learn one new thing, read it again.

Word connections/connotations and etymology of the word black:

“Aye nigga!” a Latinx shouts in the halls of Rangeview.

“Nigga you’re dumb,” an Arab jokes in his English 9 class.

“Where is that nigga?” an Asian questions in search of his friend bringing him food for B lunch.

I hear it every day in the halls and in the commons from people who are not black more than I hear it from people who are.

I see it on social media. I hear it in my classes. It is shouted at parties.

Etymology is the study of words and their origins, and how said definitions have evolved as time passes.

Linguist Aliah Luckman shed knowledge on the fact that the word black has been attributed to black people long before it before it became an addition to the English language.

Luckman states, “In 1422, Portuguese sailors first encountered the people of West Africa in search of gold, salt, and other commodities. This encounter birthed the Portuguese/Spanish term ‘negro,’ which came from Latin ‘niger,’ meaning ‘black’ or ‘dark.’”

She also claims that the word has denoted blackness.

This means that black people have long had the term lashed onto their backs, long before a color became a racial slur.

A brief history of the racial slur “nigger” in the United States:

If I discuss some brief history of said racial slur, I will obviously have to talk about racism.

According to the African American Registry (AAREG), “No matter what its origins, by the early 1800s, it was firmly established as a derogative name. In the 21st century, it remains a principal term of White racism, regardless of who is using it.”

The use of the word became more prominent during the era of slavery. It is common knowledge that even when slavery was not at its peak in the United States, white people still used racial slurs as tools to demean.

Some of the following (of many, many) racial slurs used were: monkey, jigaboo, Aunt Jemima, coon, black barbie (for black women who wanted to “look white”), cargo, bootlip (big lips), brownie and yes, you guessed it — nigger.

My ancestors were stolen, branded, beaten, sold, raped, bled out and torn from their families, yet were still hopeful in a society that was quite literally set-up for their demise.

Field Nigger.

House Nigger.

Poor Nigger.

That is my history. This is my present.

If your fragility forces you to respond that you were not your ancestors or you have X experience with X so you have struggled too, then this is the point where you put down your guard of defense and try to understand.

I will never discredit what another person goes through, but I will generalize. That is not to say I refuse to acknowledge other people’s individuality, it is just not relevant in this situation.

Why, Dominique?

“Setting aside your sense of uniqueness is a critical skill that will allow you to see the big picture of the society in which we live; individualism will not. For now, try to let go of your individual narrative… work to see how these messages have shaped your life, rather than use some aspect of your story to excuse yourself from their impact,” said author Robin J. DiAngelo.

My ancestors’ blood still runs through me, and it is why I still feel the most hatred and utter disgust as easily as any other black person would if I were to be called a nigger.

The racial slur has been used for hundreds of years to belittle an entire race of people so much that the average non-person of color (POC) could walk the streets completely oblivious to the systematic racism that black people still face because of the power the word has.

People are even scared to call me black because they feel like they will offend me because of how many negative connotations and word connections it has.

The slur was not just spoken, it was sung, it was written, it was engraved into the minds of children and adults who could not think for nor empower themselves, and here we are. You still tense up when you read the word nigger.

It is vital to note that feeling of uncomfort you get. That is the feeling telling you that you are in fact not a racist and would not think twice about calling a black person it.

How did nigger become nigga?

Luckman touches on a vernacular called African American Vernacular English (AAVE), describing it as, “a dialect of English with its own set of phonological rules.”

Similar to the use of Ebonics, AAVE is the use of dropping the -r off of the end of words.

“In words with syllables ending in the ‘r’ sound, the ‘r’ is deleted and sometimes replaced by an unstressed vowel called ‘schwa’ (ə), which sounds like ‘uh.’ ‘Four’ becomes ‘foe’; ‘Fire’ becomes ‘fiyuh’; ‘mother’ becomes ‘mothuh’…” Luckman adds.

Thus, nigger became nigga when the use of r-dropping was applied to account for the change of spelling due to the change in pronunciation.

Luckman notes that the suffix -a acts as a diminutive suffix, which attaches to words to lessen the severity of them.

It was because of AAVE and the English language itself that a racial slur was converted into a term of endearment/love (that’s my nigga), a sense of respect (yeah I know that nigga), an insult (I don’t like that nigga), and so forth.

In addition to this, the etymological history of the slur and the study of how it evolved has brought us here today. Though nigger carries the same heavy impact it did years ago and has not evolved much, nigga has.

So why can’t I, a person who is not black, say it?

Luckman says, “…it is important to substitute ‘can’ for ‘should’… When told you can’t do something, the triggering response is ‘Why can’t I?’ challenging you to search for reasons to grant you permission to go ahead and do it. Whereas when you’re told you shouldn’t do something, you react with ‘Why shouldn’t I?’ summoning caution and self-reflection—here, you’re concerned with preventing self-harm.”

If we have established that reading the word nigger makes you uncomfortable and shift in your seat, why does a diminutive suffix suddenly make everything all okay?

You just said that nigga has a lessened severity, Dominique, you retort.

Yes, but that lessened severity was not for you to decide. It was not derived from a racial slur used against you, to begin with. So what is the desire to use it? The itch for you to say just one word that is not yours to use?

Not mine? You question. How can you take a word and say it is yours?

“Nevertheless, she persisted,” is a saying that was reclaimed by the feminist movement that originally served as a political put down.

The feminist movement took a whole saying with negative connotations and word connections and turned it into a positive.

Author Carolyn Gregoire said, “Reclaiming words can play an important role in cultivating identity and facilitating conversations about rights.”

A black person who says the word, even if they do not realize it, is reappropriating it. We are reclaiming the word for our own purposes. We are taking back a word that carried such a pessimistic stigma and refusing to continue being pushed farther down into the depths of an oppressive society.

Therefore, it is not your word to say because it was not derived from a racial slur that is still being used.

Author Mackenzie Gleysteen states, “If the word is so offensive to the black community, then why does the black community still use it?”

The word is not offensive to the black community. As a whole entire race, it is impossible to account for the minds of millions, to say what does and does not go for them.

By saying it is offensive to the community, a great majority of black people would have to agree.

Yes, there are people in my community who feel as though the word should not be used at all. That is their own opinion to have because they are black.

You, on the other hand, do not get to decide what offends POC period, which means black people too. It will never be your decision to have because we have already established why you should not use the word.

Glysteen adds, “I argue that if the black community really wants to see the change in others, then the black community needs to make a change too.”

The black community is doing exactly that, making positive and progressive changes in our own community, and it will never be anyone else’s place to criticize every little action we do:

Kneeling at games and boycotting the National Football League (NFL), not standing for the pledge, peacefully protesting and reclaiming nigga from a national culture with a long history of nigger hating.

Recap:

Thus, if you are not black, do not say nigga.

If you are interested in reading the full article by Linguist Aliah Luckman, click here.

For other perspectives and more education on the term: click here, or here.